Around half the products sold in a typical supermarket contain palm oil. An extremely versatile ingredient, palm oil is found in snacks, cosmetics, household cleaners and body care products.

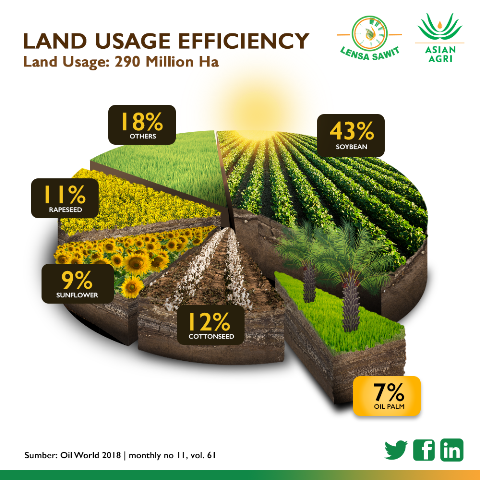

This is not without reason. Oil palms are the highest-yielding vegetable oil crops, producing more oil per hectare than rivals such as sunflowers, soybean and groundnut.

Palm oil has excellent cooking properties, being able to withstand high temperatures, and has a natural preservative effect, which means it has a relatively long shelf life.

However, use of the ingredient has been criticized over the past decade, with palm oil industry critics saying that production comes with deforestation and the loss of habitat and endangered species, forest fires, haze issues and contribution to climate change, in addition to companies’ encroachment into and takeover of land belonging to indigenous communities.

These critics have led consumers and organizations to suggest boycotts of products which contain palm oil. Early this year, the European Parliament voted to ban the use of palm oil in all European biofuels by 2020.

Yet, a complete ban on the use of palm oil will only create other significant issues. Not only would it unfairly strip millions of palm oil farmers of their livelihoods (Indonesia and Malaysia account for 85 per cent of total palm oil output globally), a recent report by IUCN states that replacing palm oil with other types of vegetable oil will require significantly more land.

Other vegetable oil crops require up to 10 times the land to produce the same volume of oil. The extra land required to replace oil palms has to come from somewhere, with deforestation an obvious risk.

Other vegetable oils also have different chemical properties, meaning they have to go through a process known as hydrogenation for use in many recipes. There is strong evidence that hydrogenated or partially-hydrogenated oils can have negative effects on health.

How then do we have the best of both worlds – keep using palm oil but without cause for guilt or regret? That’s where sustainable palm oil comes in.

The most widely accepted definition of sustainable palm oil comes from the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO). The RSPO is a non-profit certification body which unites stakeholders from all sectors of the palm oil industry (including oil palm producers, processors and traders, retailers and environmental organizations) to develop, produce, and use palm oil which minimises any negative impact on the environment and communities.

Producers who are RSPO certified must abide by eight principles: commitment to transparency; compliance with applicable laws and regulations; commitment to long-term economic and financial viability; use of appropriate best practices by growers and millers; environmental responsibility and conservation of natural resources and biodiversity; responsible consideration of employees, and individuals and communities affected by growers and mills; responsible development of new plantings; and commitment to continuous improvement in key areas of activity.

Is certification enough?

Asian Agri has been a RSPO member since 2006, and is 86 per cent certified, but the standard is not without criticism. Critics have pointed out that RSPO principles, which call for “responsible development of new plantings”, do not completely prohibit oil palm producers from cutting down more trees to create more land for palm oil production.

Asian Agri supplements its RSPO certification with its own zero-deforestation policy at its plantations, and complies with other sustainability standards including the International Sustainability and Carbon Certification (ISCC) and the Indonesian government’s Indonesia Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO) scheme.

At present, Asian Agri’s own oil palm estates are 100 per cent ISCC-certified and 91 per cent ISPO-certified.

Fadhil Hasan, Asian Agri Corporate Affairs Director, explained that different oil palm markets require companies to have different certifications.

“The food industry in Europe requires RSPO standards, while European biodiesel needs to be ISCC-certified. ISPO certification, on the other hand, is mandated by the Indonesian government. At Asian Agri, we have all three which lends the company credibility in terms of our sustainability standards,” he said.

Industry critics often blame the palm oil industry, among others, for the forest fires that have affected Indonesia in recent years, in particular the severe haze which impacted the region in 2015. Asian Agri banned clearing land by fire in 1994 – one of the first companies in the country to do so – and does not develop on new peatland areas, which are deemed to be highly flammable during dry seasons and thus prone to causing forest fires.

Palm oil has also been blamed as a driver of habitat loss for species indigenous to Indonesia, but that too can be mitigated by choosing the right areas for farming.

“Asian Agri does not clear new land for plantations, and our operations were set up in already-degraded areas with relatively low biodiversity value,” Fadhil said.

Within its plantation areas the company also does not plant on areas that are deemed to have High Conservation Value (HCV): areas with important biological, ecological, social or cultural value at the national, regional or global level.

Spreading Sustainability

Complying with third-party certification standards is a major commitment for a large company. For Indonesia’s 1.7 million smallholder farmers, who account for around 34 per cent of production, it is all but impossible. Many of them don’t even have the legal paperwork required, never mind the expertise and finance needed.

Partnering these smallholders with large companies confers a number of benefits. It helps the farmers to earn sustainability certification, reducing their environmental impact. It helps them raise their yields by using modern methods, improving their livelihoods. And it enables companies like Asian Agri to secure a larger supply of raw materials without the need for any new land clearance.

It is for those reasons that Asian Agri launched its One to One Commitment, with the aim to match each of the 100,000 hectares of its own plantations with land owned by smallholder farmers by the end of 2018.

In 2013, Asian Agri assisted the first independent smallholder group in Indonesia to achieve RSPO certification, further assisting them to also become the first independent smallholder association to earn ISPO certification in 2017 and is now applying the lessons learned though that pilot to a much larger group of smallholders.

As part of the certification process farmers are required to log information on the Fresh Fruit Bunches (FFBs) they produce, making their harvest easily traceable.

Asian Agri has achieved 100 per cent FFB traceability in its entire supply chain (which includes the FFBs it receives from smallholders) since 2017.

“To have traceability means to know your supply chain. Because we still need FFBs from outside suppliers – our smallholders – to supplement our supply chain, it is important that we know who the smallholders are and how they manage their plantations.

“In this way, we can guarantee that our palm oil is yielded from responsible and sustainable plantations,” Fadhil said.

Scale enables sustainability in other ways. For example, Asian Agri has built seven biogas power plants – with plans for 13 more by 2020 – to convert organic waste from the production process into clean energy. The electricity is used to power the mill, reducing emissions of greenhouse gases, and also provides renewable energy to the local community.

The question is not whether palm oil can be sustainable – it can – but how best to spread sustainable practices, said Fadhil.

“When it comes to palm oil, we at Asian Agri are fully committed to and confident about how we’re playing a role in the globally shared responsibility of promoting the use of only sustainable palm oil in our daily lives,” Fadhil said.